January 27th is the Day of Memory, which the UN has established since 2005 to commemorate the victims of the Holocaust and Nazi persecution. For us, it's an opportunity to remember Gino Bartali once again.

"I used to hear about him as a phenomenon. Whether it was pouring rain or a storm was blowing, whether it was forty degrees in the shade or teeth were chattering from cold, whether there was food or no food at all, they said he always went fast, no matter what and wherever. A force of nature".

Franco Cribiori used to hear about him - it was the 1950s - in the racing department of Legnano, on Via Cicco Simonetta, at Porta Genova, Milan, near the Darsena. "He was on the road between home, in Corsico, and school, the Carlo Bazzi Institute on Via Cappuccio, between his diploma as a building surveyor and the dream of cycling. I would stop, go inside, there were Eberardo Pavesi, the Avucatt, sports director, Umberto Mascheroni, whom everyone called Lupo or Mr. Lupo, and Umberto Marnati, Legnano mechanics. Inside there - the official language was Milanese - cycling was in the air, inside you went to cycling lessons of history and geography, inside you listened to stories and tales especially about Bartali. That time at the Giro, that time at the Tour, that time at Sanremo, that time at Lombardy, that time in the Alps, that time on the Apennines, that time in the Pyrenees. Bartali, capable of enduring any difficulty, fatigue, pain. A phenomenon. A fakir".

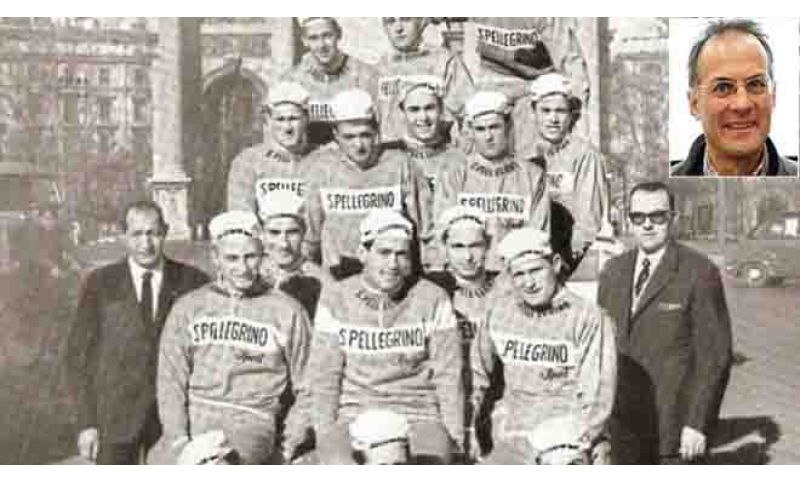

So that, when they finally met, introduced themselves, greeted each other, Cribiori already felt like he knew Bartali. "Who didn't know Bartali? He was a father of the nation, a national hero, he was cycling. I came from three winning years as an amateur at Cademartori and from the biggest disappointment of my life, a collarbone fracture 15 days before the Rome Olympics, azzurro in the road race. I joined Legnano for the end of the season, placed in the Giro dell'Emilia, Coppa Agostoni and Giro di Lombardia, remained in Legnano in 1961 nearly reaching the podium at Giro di Campania, Tre Valli Varesine and Giro del Lazio, especially the Italian championship, fourth. In 1962 I moved to San Pellegrino, where Bartali was sports director, guiding star, everything. Because he knew everything about cycling, but measured, calibrated, founded on himself. Only that he was not like us, indeed, we were not like him. Bartali would not accept that we climb the Ghisallo with a 23 when he did it with an 18 or at most a 20. He would shake his head, grumble and pronounce: you're good for nothing, you're all wrong and all to be redone".

Not entirely wrong and all to be redone, if that year Cribiori under Bartali won the Coppa Placci, was second in Giro del Piemonte, Giro di Romandia ("But only because I fell") and Giro del Veneto. "In 1963 I moved to Gazzola, they had offered me better conditions and the role of captain, and those two seasons would prove to be the best".

By now Bartali had entered Cribiori's life: "He was an institution. And when I became sports director, he was always in the world of races and riders as an opinion maker, journalist, witness, ambassador, any qualification would have been too narrow, reductive. In the evening we would often find ourselves in the same hotel, he would start telling stories with a hoarse voice and end, maybe after midnight, with a good voice, as if memories had the power to remove dust, rust, cough. And we would listen to him eager and enchanted like children when they are told fairy tales of Little Red Riding Hood and the bad wolf or Snow White and the seven dwarfs. And to think that, if it had been up to me, I would have gone to bed early, after dinner with the riders and the round of rooms I would have gone to bed early, with newspapers to review the stage already lived and the Garibaldi to study the stage yet to be lived".

Among the stories Bartali would tell was always Coppi: "He would speak of him with respect and perhaps also with nostalgia, after the years of rivalry the years of friendship had arrived". Among the stories Bartali would tell was also the war: "Of when he helped partisans by carrying orders and when he saved Jews by hiding documents in the bike's seat tube, even making 300 kilometers round trip and challenging roadblocks. But he would not publicize these memories, he would only confide them to those he trusted, those he was friends with, those he knew would not then gossip".

Different times, different cycling. "Different world - Cribiori sighs -. Today there's a lot of talk about artificial intelligence. But can you trust artificial intelligence more or the generous and just human intelligence of a Bartali?" He doesn't wait for an answer. Cribiori. Perhaps it wasn't even a question.

Se sei giá nostro utente esegui il login altrimenti registrati.