He taught us that tears can also be of joy. He taught us that crying can also be about happiness. He taught us that to win, you must first dream, and that if dreaming doesn't help you win, it at least helps you live. So much so that he was one of those who, without fear of contradiction, could say he had lived: not one, but two or three lives, perhaps even four or five. Without brakes on the bike, without brakes off the bike. Full throttle, all out, until death.

Michele Dancelli has died. It seems impossible, because Dancelli was one of those names, one of those faces, one of those riders who seem like they should never die, like Mick Jagger in rock, like Tom Sawyer in literature, like Sandokan in cinema or TV. Right on TV, during a "Race Verdict" show, Sergio Zavoli invited Pier Paolo Pasolini, but then had Vittorio Adorni interview him. Pasolini said, "I came here simply out of love for cycling. However, being here, as always happens, surprises arise, unexpected things. For example, I saw two faces I would truly use in a film: Dancelli's face and Taccone's face".

Dancelli was 83 years old, he could have been 38 or 138, the announcement of his death would have caught us by surprise, unprepared, in denial. From Castenedolo, Brescian in accent, in mind, in soul, and his fellow townspeople, all Brescians, had understood this immediately. And in Brescia, "The Club of the Poor" was born, located in a cyclist's shop, with about twenty members, three cyclists to support, obviously from Brescia: Mario Anni, Davide Boifava, and Michele Dancelli. "The Club of the Poor" mobilized for training and races, supplies and dinners, aperitifs and snacks, bets and trips. On one occasion, the shop owner, Pietro Serena - admired because he welded frames without using gas bottles - like Enzo Maiorca in diving, like Reinhold Messner in climbing - participated in the outing. It was the Milan-San Remo of 1970. Dancelli's very own. Who knows what would have happened to Dancelli's career if Serena, the lucky charm, had taken a liking to it. Instead, that was the first and only time, amen.

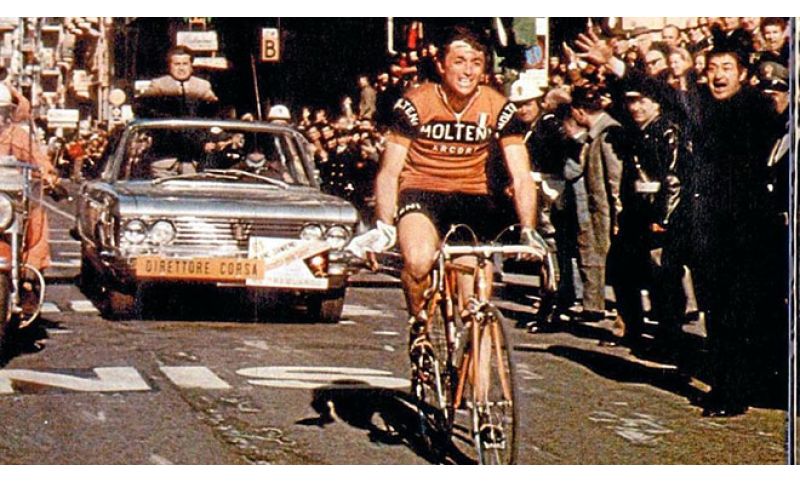

The Milano-Sanremo of Dancelli, as if the other 237 riders didn't exist. "Dancelli - Ernesto Colnago told me - was an instinctive, impulsive rider who did crazy things, like breaking away from other escapees near the finish. He believed company was cumbersome and was convinced someone would attack, so he might as well attack first. And that's exactly what he did that day on Saint Joseph's feast day. It happened at a sprint point in Loano, 218 kilometers from the start and 70 kilometers from the finish. Carletto Chiappano, a Molteni domestique, led out Dancelli, then moved aside, fiddled with his gears, showed or feigned a mechanical issue, raised his arm to signal the team car and created a gap. Dancelli continued, stretched out, escaped. Twenty meters of advantage became 50, then multiplied to 100. Those behind studied the situation. Goodbye.

I remember Giorgio Albani shouting at Dancelli to eat sugar, I remember Piero Molteni promising 'if you pull this off, I'll give you the entire factory', I remember myself praying that Michele wouldn't have a mechanical issue or a puncture, ready to jump out of the team car like a sprinter from the starting blocks. In fact, to be even more prepared, I put the spare bicycle on my shoulder". Dancelli would win by 1'39" over Karstens, Leman, Zilioli, and Godefroot. Seventeen years after the last Italian victory. The Milano-Sanremo seemed cursed. Dancelli was more powerful than any hex or spell.

Dancelli was the best of youth. The seventh of seven children (eighth if counting a little brother who died in infancy), orphaned of his father (who died of pneumonia when Michele was one year old), he started in Castenedolo among chestnut trees and vines, with thefts and heroism: in 1943, the bronze church bells were dismantled by Germans for casting, and the following night they were brought back to the village and hidden until the war's end. A bricklayer at 14, his first bike - a blue Condor - used to go to and from work, 10 working hours followed by training until late at night, his first Giro d'Italia - as a spectator - at 14, when he heard the caravan's horn and quickly abandoned his trowel and wheelbarrow to run to the roadside, his first race at 16, his first victory at 19 in the Italian CSI championships. And from the start, always, that anarchic racing style of an attacker that would make us fall in love with him. Twelve professional years from 1963 to 1974, 73 victories, pink jerseys, national and azzurra jerseys, with two world championship bronzes. He could win - and did win - in every way: in sprints and breakaways, uphill and downhill, in line races and stage races, in classics and circuits. He was a loose cannon, a lottery ticket, an ace up the sleeve. He was Giamburrasca, Pierino the Pest, Masaniello. A joker, a Garibaldian, a wild horse.

He was also a hothead. On and off the bike. In 1966, during a ride in the Ligurian hinterland, he and Gianni Motta encountered a blonde who was interested in both of them. After an unexpected intimate encounter, they later learned from a local that the woman was ill, prompting them to rush to the hotel to gargle with denatured alcohol.

Dancelli's unpredictability, both in and out of racing, had become predictable and proverbial. He even managed to forget a promise to the Pope. It was Pope Paul VI. During a private audience in 1968, Giovan Battista Montini, a fellow Brescian, asked Dancelli a favor: to bring greetings to the Dancelli inn in Pezzoro when passing through. Michele fulfilled this request 30 years later, during a traditional spiedo lunch.

He was made in his own way, Dancelli. That time in Belgium during the Paris-Luxembourg race, with Salvarani and Molteni in the same hotel - while Felice Gimondi and his domestiques kept to a strict diet, Michele and his teammates went out for roast rabbit. Result: Molteni narrowly missed victory, and Salvarani finished last.

Dancelli inspired not just passionate followers and sensitive women, but journalists and writers. Bruno Raschi, "the Divine", captured "his bloodless face illuminated by rage"; the cap thrown into a carnation field when it became a rag of sweat; his leg muscles, dry and sculpted by effort like a Donatello. Gian Paolo Ormezzano musically dubbed him "din, don, Dan...celli". Gianni Mura defined him "a nomadic dreamer". Gino Sala elected him "rebel".

"Will the critics now give me the champion's license?" Dancelli asked on the podium of that 1970 Milano-Sanremo. Of course, Michele. But come back and have an orange soda with us. The joke is best when it's short.