Perhaps Bjorg's death could truly save his colleagues. His name was Bjorg Lambrecht, a young professional cyclist from Ghent, who showed great promise: second at the Under-23 World Championship in 2018.

On August 5, 2019, during the third stage of the Tour of Poland, he was involved in a terrible crash near Pawłowice, ending up in a ditch. Rushed to the hospital, he died in the operating room at just 22 years old.

This tragedy changed the life of Flemish engineer Bert Celis, who from that moment dedicated himself to studying a way to protect cyclists. Because the helmet protects the head, yes, but the rest of the body is covered only by an extremely thin fabric: and few sports are as risky as cycling.

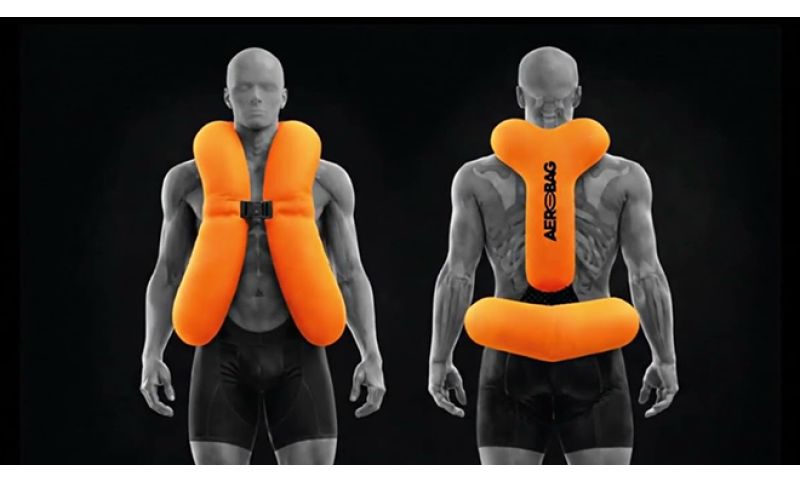

There has been talk for some time of an airbag system to better protect cyclists, similar to the one already used in MotoGP. But developing one, adapted to the specifics of cycling, has taken time. Problems of weight and bulk, first of all. Now, after years of research and development, a breakthrough is finally on the horizon, and engineer Celis has presented his Aerobag, a system introduced a few weeks ago during training. We talked about it a few days ago and now we'll go into details with its inventor.

"Professional cyclists from the Dutch team Picnic PostNL have started testing it," says Celis. "We're waiting for feedback from cyclists and then we'll see if it can actually be brought to races in 2027: this will also require a regulatory framework from the UCI."

How does it work? The Aerobag is relatively light (500 grams) and can be completely integrated into cycling clothing. "On the back, there are a CO2 cartridge and sensors that detect an imminent fall," Celis continues. "The system is based on three parameters: back position, rotational acceleration, and lateral acceleration. The combination of these three values indicates to the device whether a cyclist is falling or not."

If a fall is detected, the CO2 cartridge explodes and the airbag fills with air. From the center of the back, it travels around the neck to the torso and finally to the hips. In just a few milliseconds, the airbag inflates to a thickness of 8-10 centimeters, cushioning the cyclist's fall and stabilizing the neck."

Celis is a materials engineer and in the past has also built a wind tunnel in Beringen, Belgium, where several professional teams have conducted tests. "I once saw Lambrecht pass by us, just a few months before his fatal accident. That was the stimulus that pushed me to start working on this."

Thanks to his experience in the world of cycling, Celis was able to take into account as much as possible the needs of riders in designing the Aerobag. "We know that cyclists often want to continue pedaling as fast as possible after a fall. That's why the pressure in the airbag slowly decreases after a few seconds and automatically returns to its original shape. Anyone who still wants to remain protected can, in principle, simply connect a new CO2 cartridge to the system."

And further: "The Aerobag is currently configured quite conservatively. This means that, in practice, it will not detect some falls: for example, with a slide in a fast curve, the rotational acceleration will be too low to activate it. But this choice is intentional. In any case, if the Aerobag inflates regularly without a fall occurring, cyclists will not be trapped, because you can continue pedaling without any problem."