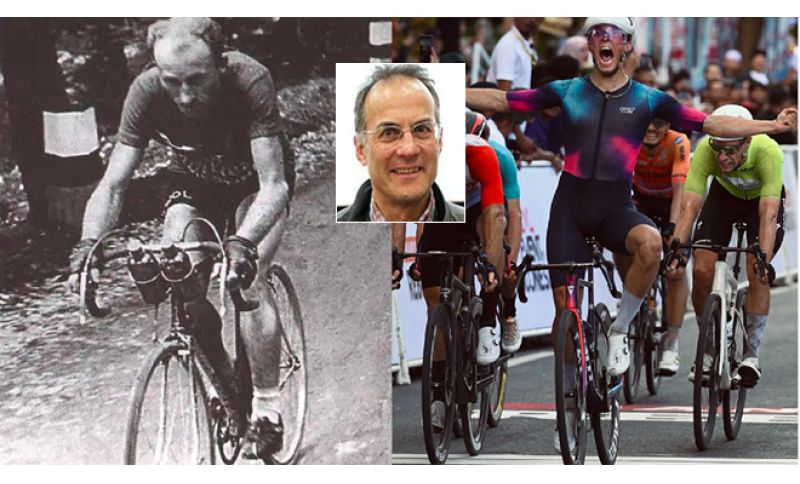

Tour de Banyuwangi Ijen, in Indonesia, last Monday. Second stage, Alaspurwo-Banyuwangi, 158.8 km. First, in a sprint, Francesco Carollo, 25 years old in 17 days, from Como, of the Swatt Club. A winning Carollo. Almost a contradiction, an oxymoron, a paradox. Because until now Carollo was a symbol, a synonym, an emblem of the last. The last of the last. The very last. More last than Luigi Malabrocca.

It was the Giro d'Italia of 1949. Three days before the start, while working on the roof of a public housing, he received a telegram: he had to report as soon as possible to Palermo to replace the flu-stricken Fiorenzo Magni, captain of Wilier Triestina. He went home, filled his cardboard suitcase given by the team, apparently also stuffing a couple of Merlot bottles, jumped on the first train and in a couple of days managed to reach Sicily and join Cottur and Martini, Bresci and Maggini, Ausenda and Feruglio.

Carollo was 25 years old. Sante by name, but everyone in the village - Montecchio Precalcino, in the Vicenza area - called him Santo. And Càrolo by surname, but through a transcription error became Caròllo. Second of four children, extremely poor childhood, laborer and bricklayer, only a couple of years earlier he had fallen in love with the bicycle, obtained a loan from a friend and bought one, just one year as an amateur, a prestigious victory in the Schio-Ossario del Pasubio, and immediately, now or never, the transition to professional cycling. His first races served to get familiar with the right distances. At the Milano-Sanremo, 78th almost 22 minutes behind Fausto Coppi. At the Giro del Piemonte it went worse: after two punctures, left with only one pump, he accepted a wheel from a sports enthusiast along the route, but the regulations forbade it, the penalty was a three-month disqualification, and Sante Carollo (I call him this way) took up trowel and mortar again, limiting himself to some evening bike rides. Until that telegram.

In the first stage, Palermo-Catania, Carollo finished last, over an hour behind winner Mario Fazio and three-quarters of an hour behind Luigi Malabrocca. "If the group exceeded 30 per hour, I would lose contact and proceed detached from everyone - wrote Benito Mazzi in the indispensable "Coppi, Bartali, Carollo and Malabrocca" (Ediciclo, 2005) -. How much solo cycling I did. It was self-respect that kept me going, made me grit my teeth. And the doctor Campi, the Giro's doctor, helped me with his care, his proximity. I started pedaling a bit like a Christian after six, seven stages, when my name was popular because associated with the last position, with great gaps". Malabrocca, who had invented the black jersey by conquering the last place in the 1946 Giro (4'09"44 behind Gino Bartali) and repeating the feat in the 1947 Giro (5'52"20 behind Coppi), skipping the 1948 edition for manifest superiority (in inferiority), was convinced that his rival would withdraw. When he realized that he would instead persist until the final Milan finish line, Luisìn began to worry and devise ways to detach him from behind. Two extraordinary endurance riders. Two marvelous extremists. Two historical revolutionaries. Two formidable... finishers.

If Malabrocca was tenacious in seeking solitude at the back of the group, that is, behind, Carollo sometimes yielded to the temptation of a breakaway - from his point of view - on the wrong side, that is, ahead. Like in the Genoa-Sanremo, when in a lull he went into a breakaway, accumulated a significant advantage over the group and even hoped to win the stage. Like in the Sanremo-Cuneo, on the Col di Nava, when he wanted to prove his climbing qualities, but - unfortunately for Malabrocca - was stopped by the team car to wait and help Martini with a puncture. Like in other stages when his fans would write or implore him to abandon the last position, promising him "romantic nights with splendid girls" and sending him "photographs of provocative blonde women in Adam's costume". Along the way, Carollo did not lose sight of the last place and Malabrocca, despite strategies and stratagems (his strong point: hiding and waiting), was finally forced to succumb. Phenomenal last Carollo at 9'57"07 behind Coppi.

Carollo's career was very short: it lasted only that year. He managed to show signs of his climbing skills, winning the Mountain Grand Prix of the Tenth National in La Spezia (and on the bastion of Fosdinovo he had even preceded Sandrino Carrea, Coppi's gregario). Not confirmed by Wilier, not hired by Bianchi (it seems the Campionissimo wanted him with him), Carollo sold the Mosquito (a pedal-powered motorino) to pay for his trip to Switzerland and work as a bricklayer with his father.

So the other day, in Indonesia, that first Carollo sounded strange, surprising, unprecedented. And very poetic.

Se sei giá nostro utente esegui il login altrimenti registrati.