Jean Stablinski, his team captain, used to call him Coppi. But what Coppi, he would reply. Coppi was not a domestique, did not carry water bottles, did not push, did not live like an emigrant, did not suffer from homesickness, did not torment himself with the hope of one day buying a house for his family or opening a cyclist's shop.

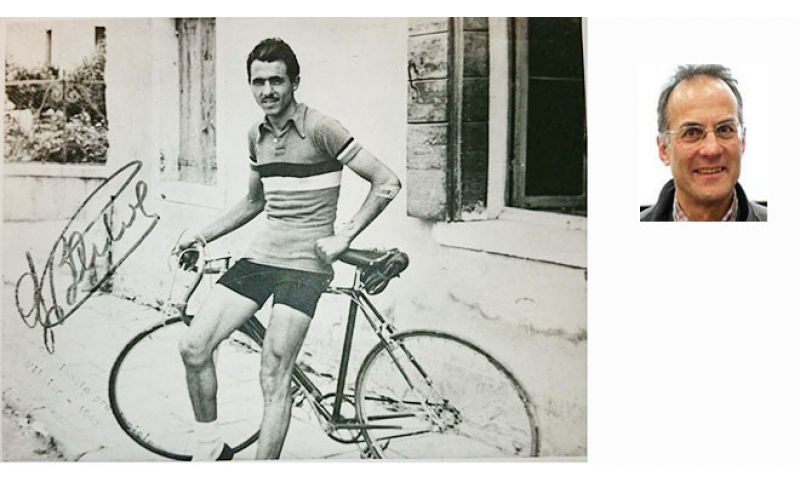

He was Mansueto Semenzato. And when he explained he was not Coppi, he was far from meek. From Spinea, Venice, born in 1926, Mansueto had started racing imitating Bevilacqua, continued racing inspired by Bartali (in Semenzato's photo there's Bartali's autograph!) and distinguishing himself from Coppi, insisted on racing while dividing his time between work in the mine (and Stablinski understood, he too had been a miner) and bicycle races, at least once feeling like Bevilacqua or Bartali or even Coppi when winning the Paris-Lille. He had the gift of talent: he triumphed by a wide margin the first time he wore a race number, as a junior in a race open to amateurs. He also had the gift of being content: he was happy when Arbos offered him a contract, with no salary but expenses paid and a jersey given.

Yesterday, Mansueto Semenzato would have turned 99 years old. Moreno, one of his seven children, the closest to becoming a professional rider, reminds me every March 15th with the affection and gratitude that Mansueto deserved for his passion inversely proportional to his glory. The passion with which he pedaled as a domestique even for Cottur, the same passion with which he continued racing as an independent and amateur, with which during World War II he fought as a partisan and managed to throw himself from the truck when arrested by Germans and save his life, or with which he thwarted a theft after a shootout as a security guard.

Se sei giá nostro utente esegui il login altrimenti registrati.