Claudio Michelotto was so reserved that his death was only known four or five days later. So reserved, so silent, so shadowy, so lunar. From Roverè della Luna, about thirty kilometers north of Trento, where the Adige River creates a moon-shaped bend near an oak forest. He would have turned 83 in four months. Today he would have been considered a champion, but back then, in the era of Adorni, Gimondi, Motta, Zilioli, Bitossi... and especially Merckx, emerging was prohibitive. And almost forbidden. Michelotto was - words written in L'Equipe - an unexpressed talent.

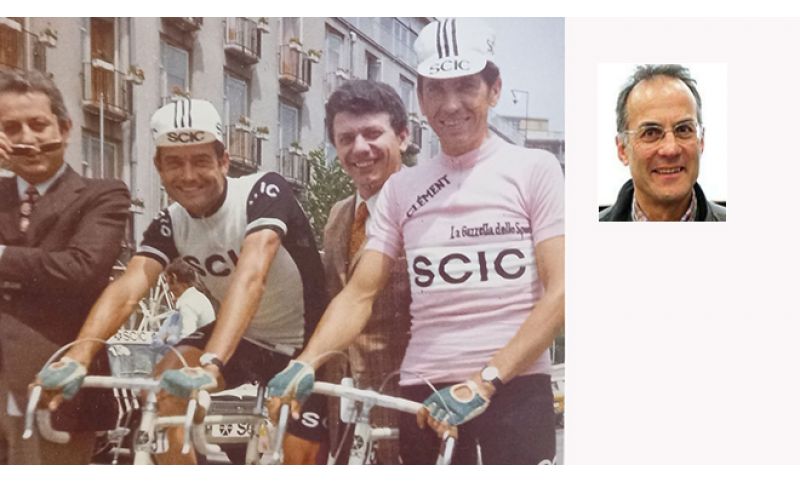

Unexpressed, but only up to a point. Ten days in the pink jersey, Michelotto. It was the 1971 Giro d'Italia. The Pink Race was climbing from the south: Lecce, Bari, Potenza, Gran Sasso. At Casciana Terme, Michelotto took the lead from his fellow countryman, Aldo Moser. He maintained it even when he crossed into Yugoslavia and Austria. The seventeenth stage revealed the eternal Glossglockner, Gimondi attacked and was accused of favoring the foreigner, the Swede Gosta Pettersson, and harming his compatriot, Michelotto. Michelotto was punished and humiliated - a one-minute penalty - for pushing. Scic, his team, threatened to withdraw. Vincenzo Torriani intervened forcefully (he wasn't the type to fold), Scic and Michelotto remained in the race. The eighteenth stage took the riders from Lienz to Falcade, 195 kilometers and four mountains to climb, Tre Croci, Falzarego, Pordoi, and Valles. Michelotto started with a 1'22" advantage over the "old man" (Aldo Moser was 37 years and four months old) and 2'02" over Pettersson. Gimondi attacked again, Pettersson followed him to the finish, Michelotto fell on the field, descending from Valles, and arrived at the finish line bloodied, almost 10' behind his rivals. "That's life - he syllabized -. I didn't sleep, I was feeling unwell since this morning, a puncture caused the tumble. I wanted to do well, these are the roads of my home. My rear tire went flat, the bicycle swerved, I flew onto the asphalt, rolled down about twenty meters. I was bleeding a lot, I tied a handkerchief roughly, continued in a 'trance'. But the frame was bent, the brakes weren't working, at every turn I was forced to drag my feet on the ground. I changed bicycles, in the last kilometers I only felt the blood running down my face. Then I ran out of strength, I didn't understand anything anymore". He dropped to ninth place overall. The next day he abandoned the Giro. There was also talk of a war between kitchen cabinet makers: Gimondi for Salvarani, Michelotto for Scic, Pettersson for Ferretti.

Shy, but never a slave, Michelotto had been an azzurro among amateurs (on the team when Gimondi won the Tour de l'Avenir), from 1966 to 1973 among professionals, captain, lieutenant, free rider, but always a true cyclist. Winner of short stage races (Tirreno-Adriatico in 1968, Giro di Sardegna in 1969), winner of Italian classics (Agostoni in 1968, Laigueglia and Milano-Torino in 1969, Campania in 1971, breaking away from sprinters a kilometer from the Arenaccia stadium), stage winner (one in the Giro d'Italia in 1971, one in the Tour of Switzerland in 1972), leader in mountain classifications (in the Giro d'Italia in 1969). A climber, but also a time trialist, he couldn't be asked to win in a sprint, it wasn't his strength. His strength was consistency. His weakness was bad luck. Falls, not just the one on Valles, but also in Zurich in 1966 and at the Tour in 1970, devastating, dramatic, leaving scars and doubts. And misfortune, Giro d'Italia in 1967, the Dolomite stage ending in Trento, his Trento, on Corso Buonarroti, a lone man in the lead, him, "Michelotto has dropped his teammates" announced the speaker, then a mistake, Michelotto crashing into a hay bale, Adorni flying to the finish and Anquetil in the pink jersey.

After hanging up his number, Michelotto left cycling, but never the bicycle. He ground kilometers, ruminated thoughts, digested regrets. He was never seen at races. He escaped journalists. Shy, as already said and repeated, as well as mild and educated. Franco Sandri with a Facebook page and an exhibition in Roverè della Luna, and Diego Nart in the book "Beyond Francesco" have taken care of preserving his memory, telling his career. A dignified silence until the other day, when he left, during the Giro, without wanting to disturb, without wanting to steal space from heirs who ignored his value.